While handling an object today, we read how it will have changed within a month and hear

someone announcing what will have replaced it within a year. Simultaneously. Yesterday’s

trends are a distant memory, made obsolete by today’s, which, in turn, are already being

challenged by some prophesying guru. A whirlwind of information and, it must be said,

accelerated obsolescence. The obsolescence of products, services and ideas.

But was it always this way? A swift look back at the past suggests not. It’s the subject of heated

debate: productivity in the workplace. Especially productivity in office spaces.

The discussion – now unremitting – between designers, architects and experts, enriches us all

but also gives us pause for thought. Maybe not every innovation is actually new.

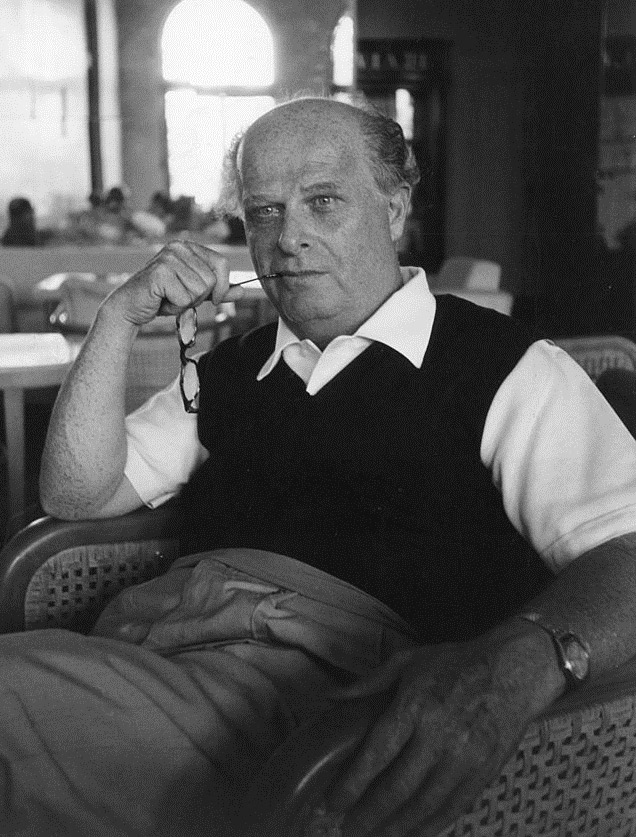

Almost 60 years ago Adriano Olivetti passed away. The measures he took are now once again

in vogue. The concepts of Ethics and Social Responsibility, which this truly enlightened

businessman was the first to introduce into his company, have inspired the corporate social

responsibility programmes of many listed and non-listed companies.

To answer this question, let’s widen the discussion a moment from the office to the factory,

which in any case incorporates offices. Adriano Olivetti had his own notion of the factory.

Not simply a place containing machinery and personnel at work. The factory’s guiding

principle is that it should be an agreeable space to work in, not one to be endured.

To the utter amazement of his father – an old-style industrialist – Adriano gave instructions

to replace the walls of his family’s factory with clear glass, permitting views of the surrounding

landscape.

He worked with architects, town planners and sociologists. He shared his vision with

them, and, in exchange, asked them to design and construct buildings and reorganise

environments and spaces able to reconcile formal beauty with functionality.

An improvement in working conditions at the company and in the quality of life outside.

His ideas on profit also challenged the trends of the period – which, we should remember,

was the 1940s. He was a pragmatist, profit wasn’t to be disregarded. But its primary purpose

wasn’t the accrual of wealth as an end in itself, but the use made of it. Profit was the fuel for

creating social value.

Olivetti invested a great deal in education and training, setting up a library in rooms at the

company that was open to all his employees. He invited intellectuals to his headquarters in

Ivrea and organised events to raise awareness, especially among young people, of solidarity,

community and culture.

What was the objective? To create wellbeing for the community.

And the factory, the workplace, became a place for sharing and for meeting, a precursor to

the movement for quality, which rotates around a fulcrum: people.

Because Adriano Olivetti placed great importance on defining an organisation of labour that

derived from the Ford model yet deviated from it by shifting its core focus from the product

to the individual. His main ambition was to seek to combine ethics and production, to unify

modernisation and humanism.

To work in an equable climate – people work better in a positive environment.

Productivity increases, sales and profits rise. The Olivetti factory became known outside of Italy.

The industrial product, already useful, became beautiful.

“I want my Olivetti to be not just a factory but a model, a lifestyle.

I want it to produce freedom and beauty because those things, freedom and beauty, will

tell us how to be happy.”

Adriano Olivetti.

The challenge of our time is thus rooted in ideas that come from the past. And it is to these

ideas we turn for the inspiration that enables our work to be realised. In saying this, we think

of the criteria with which we envisaged the holistic office, la Piazza, as a whole and in its

individual components.

Environments that inspire. Environments that help the rush of ideas. So that the people that use

them experience a sense of wellbeing in performing their daily tasks. And perform at their best.